Few names are as evocative of the exoticism of the oriental world as Samarkand and Bukhara. Oasis cities at the heart of global trade for millennia, in my mind, these names mustered up images of dusty yet splendid Islamic architecture, and bazaars teeming with the great diversity of peoples and products of the silk roads. Add to the picture caravans crossing desert plains, and the life-giving trickle of irrigation canals watering fertile oases.

The isolation of these cities from the western world, geographically, politically and culturally, meant that additions to my exotic mental vision of this part of the world were limited to a few tidbits of information on Uzbekistan’s resource riches and obscure dictators ruling since the breakup of the USSR.

Stepping into the silk road cities of central asia has been on our radar for years, and we were excited to join Nathalie, Margot’s Mum, for three weeks touring Uzbekistan. Yet on reflection, our desire was perhaps more to step into a world of our imagination, somewhat based in history. The reality of these cities today certainly carries traces of our exotic visions, but is also radically transformed. Transformed by decades of soviet rule, by the subsequent post independence period of iron fisted state control led by Islam Karimov, and by the recent onslaught of mass consumption and mass tourism.

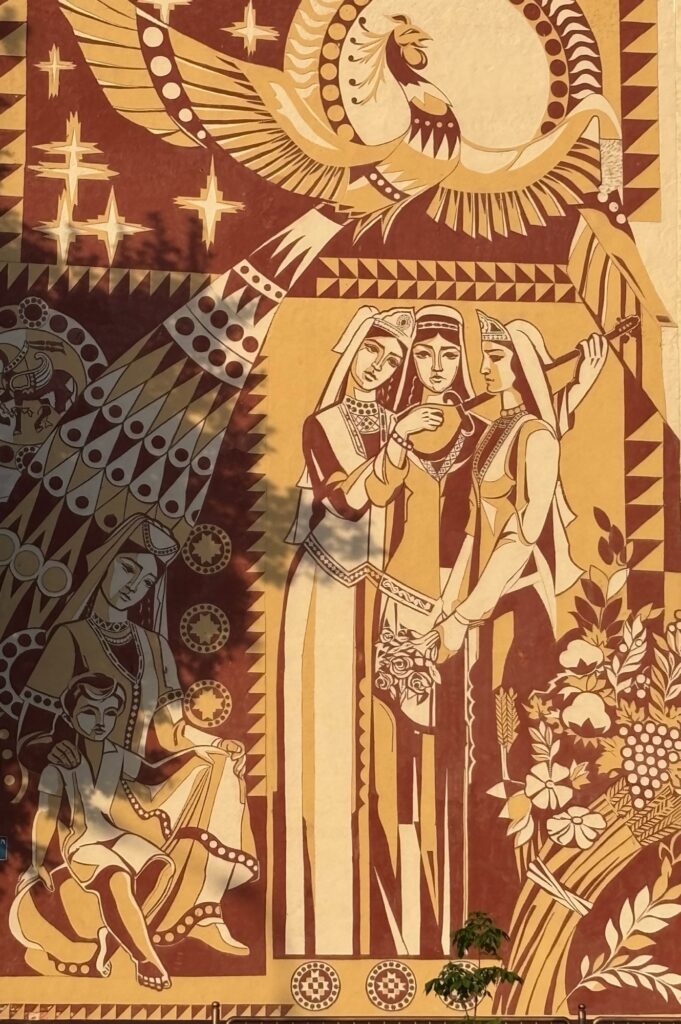

Our first surprise was Tashkent, once the fourth biggest city in the Soviet Union, and now a sparkling clean modern capital replete with a magnificent Soviet era metro system and wide tree lined avenues. A bustling bazaar, charming soviet period apartment blocks and public buildings adorned with mosaics and motifs inspired by the region’s history, stand alongside an increasing number of soulless modern buildings and shopping malls. With almost no street food and a sterile streetscape, the city felt lifeless and controlled in comparison to everything we’ve seen on the trip so far. We were excited to move on to the Silk Road cities…

Samarkand certainly wasn’t lifeless, bustling with thousands of tourists from across Europe on package tours, as well as roaming squads of golden toothed babushkas. Arrival into a land full of tourists, souvenir stalls and tourist restaurants, with the accompanying price jump, came as a shock to us after Pakistan and Xinjiang. It felt like being at a European destination on a summer weekend.

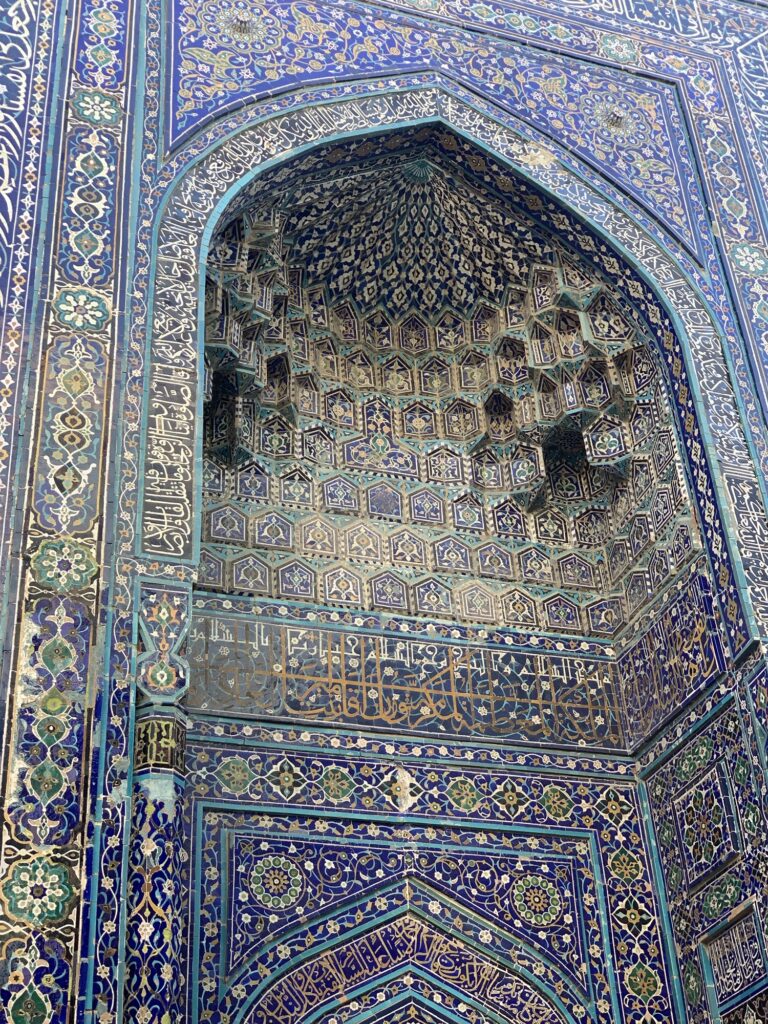

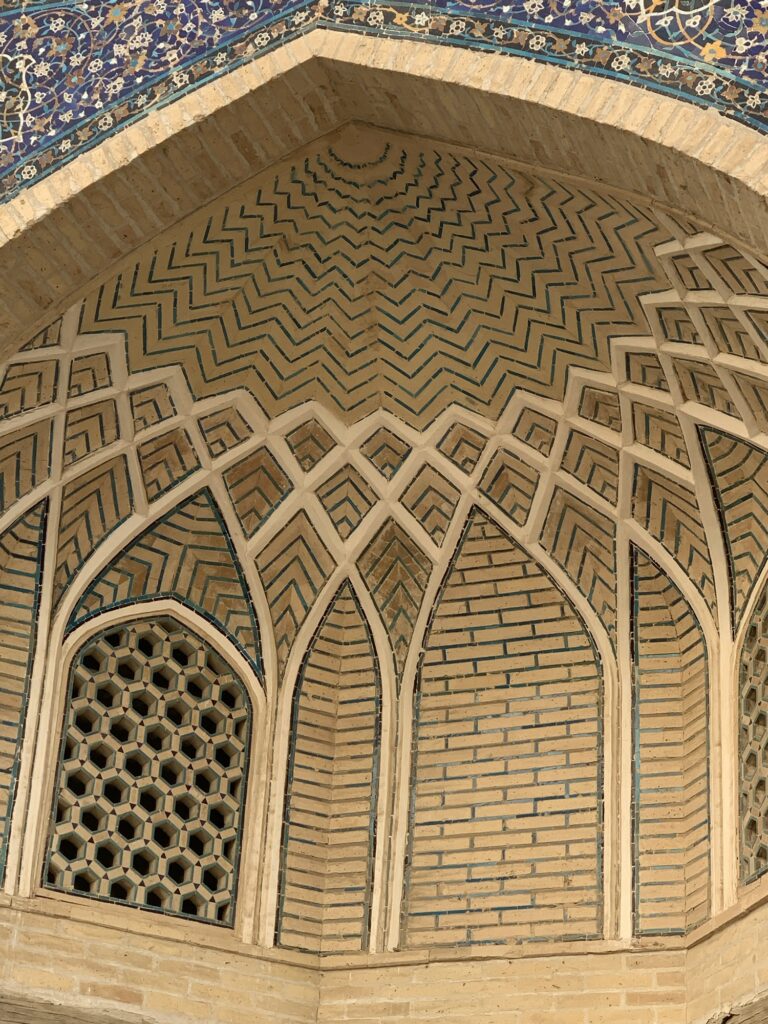

Nonetheless, these silk road cities are undeniably magical, and moments of wonder and discovery were plentiful during our time in Uzbekistan. Early one morning I ran through the quiet streets of Samarkand, past the towering blue mosaic covered domes of the Bibi Khanaum mosque, and the intricate oriental wonder of Hazrat mosque, both jewels of Timurid and later Islamic architecture. Beyond lay a land of rolling green hills dotted with poppies and other spring flowers. The rolling green hills are all that’s left of the city of Afrasiyab, or Markandia, the ancient Samarkand described by Alexander the Great and razed to the ground by Genghis Khan in 1220. Magnificent frescoes of the Sogdian king receiving ambassadors from China, Tibet, Persia and beyond have been unearthed here. I felt childlike excitement spotting the layers of bones, bricks, charcoal and pottery shards that represent thousands of years of civilization, and, with the help of chat GPT, identifying sparkling pieces of pre-Islamic glass. The magic of the site was enhanced by its abandon, far from the tourist trail and the government’s restoration and beautification campaigns; flocks of fat tailed sheep now graze here, kids kick footballs, rubbish blows around, and in the distance, the domes of the Registan madrassas rise above Samarkand.

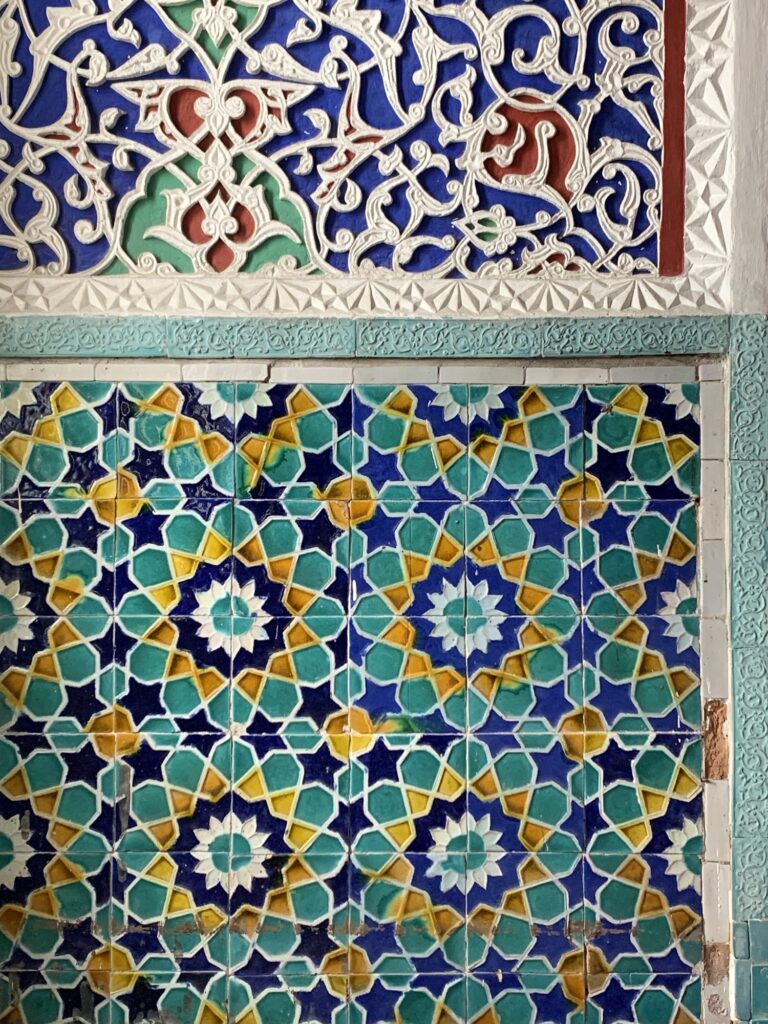

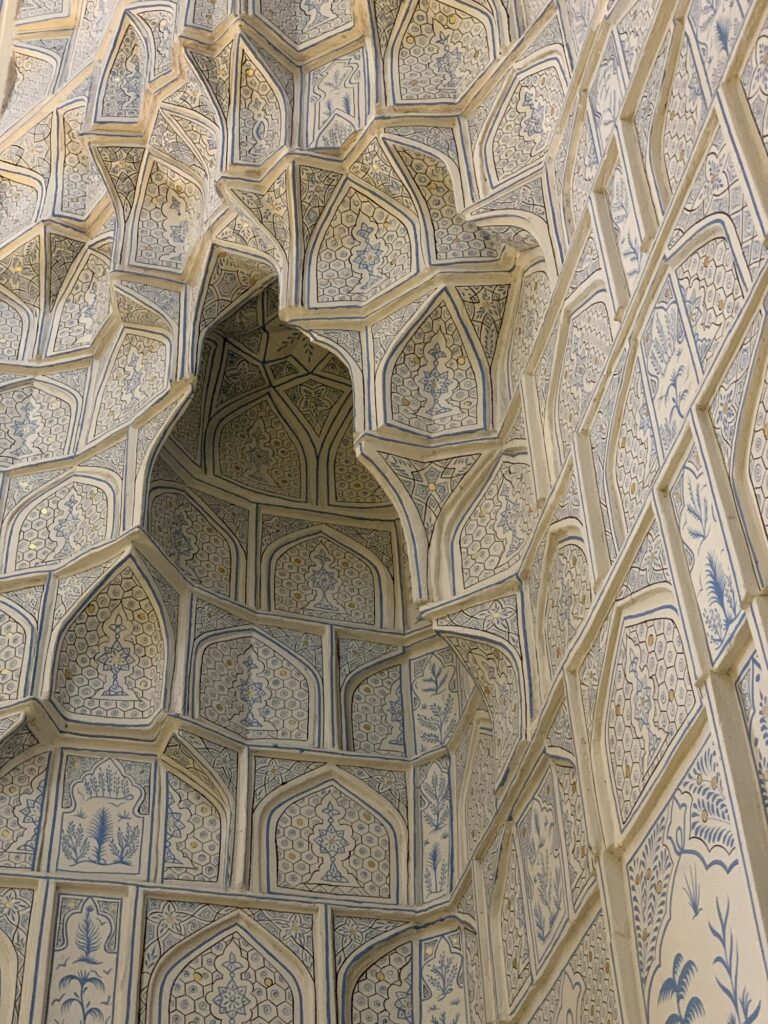

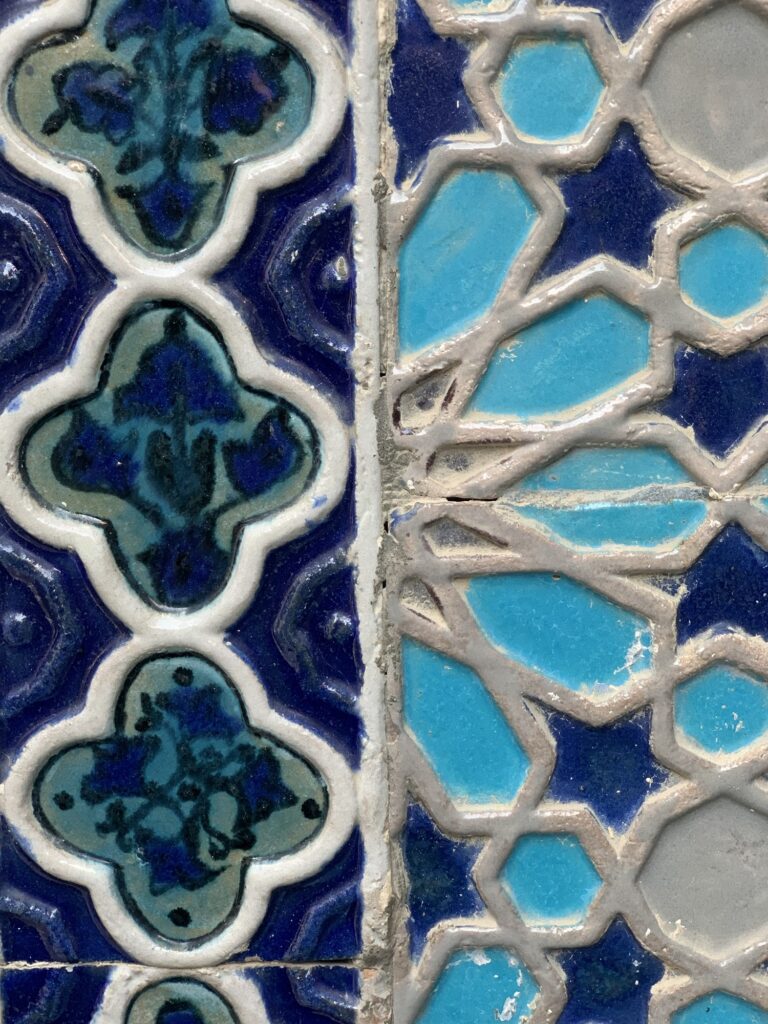

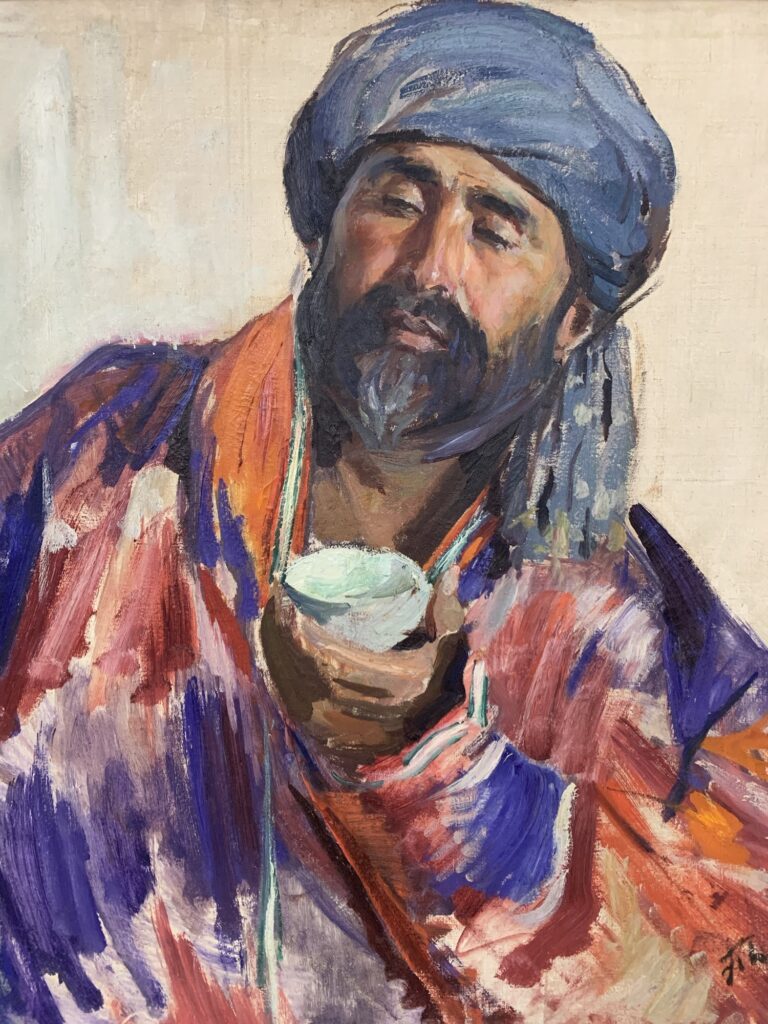

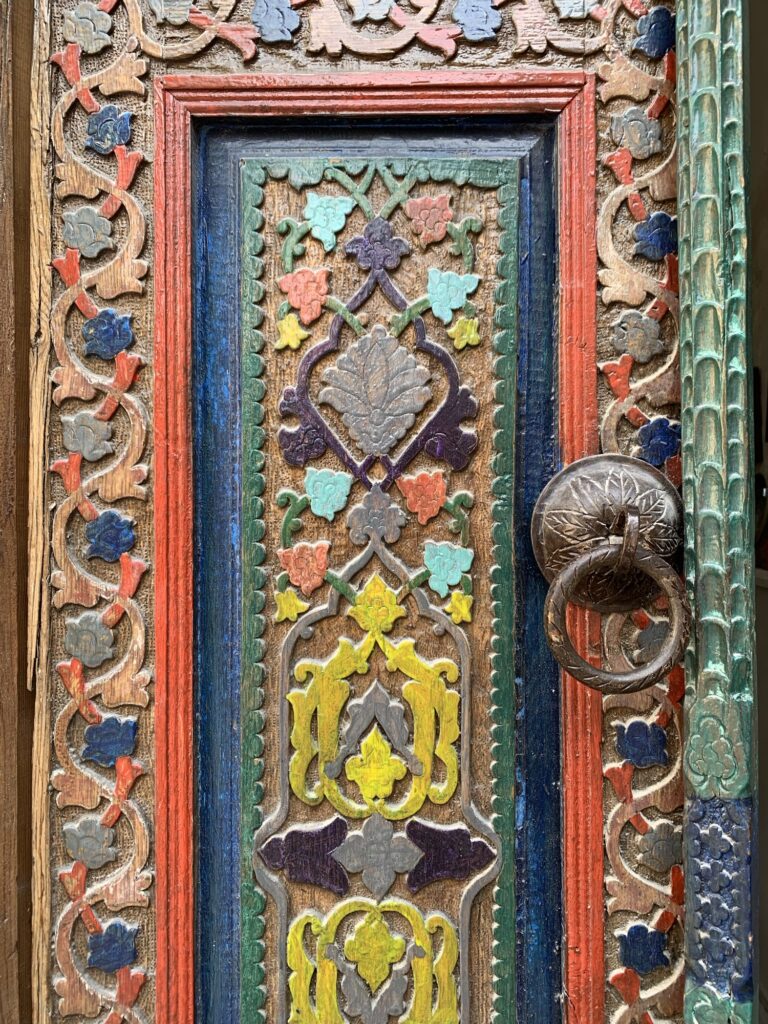

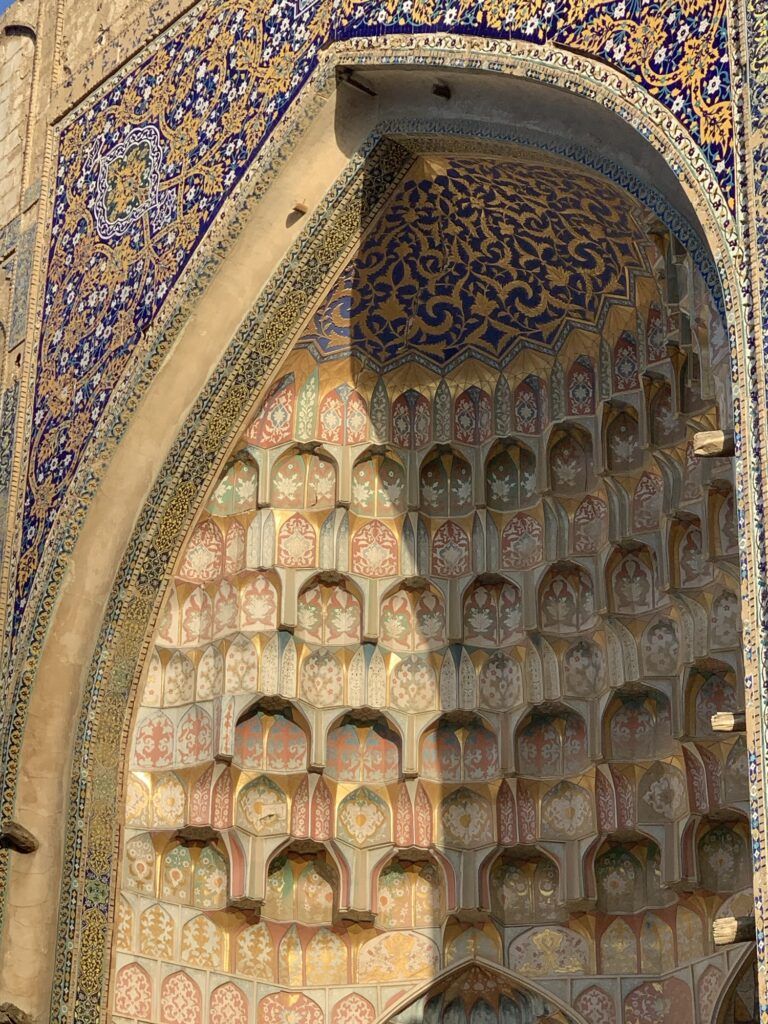

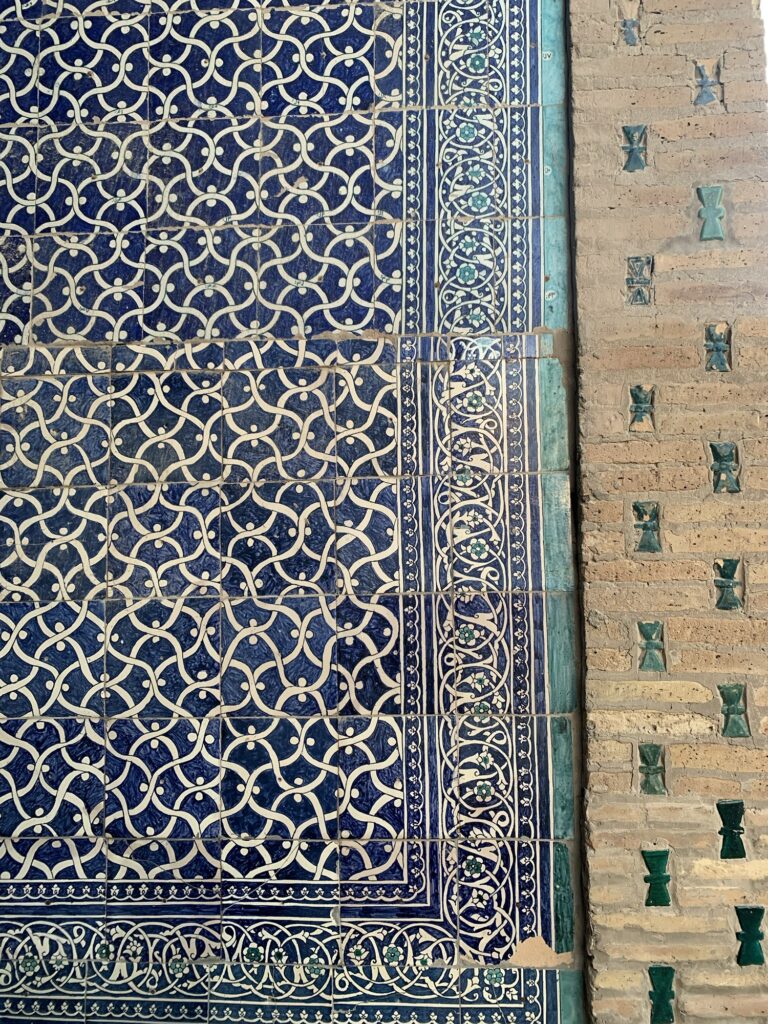

We found ourselves captivated and absorbed by many of the mosques, madrassas, minarets and bazaars across Samarkand, Boukhara and Khiva, the crowds of tourists around us seeming to disappear. These monuments manage to combine grandeur and perfection in their proportions and dominance of the local skyline, with exquisite fine detailing. Intricately carved, painted and glazed majolica tiles cover walls, domes and arches, with cobalt and copper based glazes giving magnificent hues of blue, turquoise and green. Each tile is a unique work of art. The arabesques and quranic inscriptions of the tiles also feature in magnificently carved wooden doors, pillars and furniture, while the pomegranate « tree of life », magnificent birds and flowers adorn suzani silk embroidery fabrics, carpets and miniature paintings.

It was heartening to see that many of these artistic traditions are maintained. This is largely thanks to the tourism boom: bringing customers that value handmade unique products (more than locals seem to), and motivating the government to restore historical buildings (somewhat carefully, sometimes over the top).

Outside of the cities, we spent a magical few days in the Nurata mountains, meeting up with our friends Amélie and Constance. Rising out of the arid steppe to 2000m, snowmelt and scarce rain across the mountains percolates through the rock and emerges in cool clear streams, supporting oasis valleys shaded by walnut and mulberry trees. The Uzbeks love their carpet covered outdoor daybeds for lounging and eating, many of these sat in paradisiaque settings in meadows or straddling trickling streams. Running and hiking through these mountains we encountered vultures, wild boar, wild sheep and young foals taking their first steps in the spring pastures.

This bucolic paradise contrasted sharply with the desert and desolation in the area of the Aral Sea. Only a tiny fraction of the former Aral Sea remains, with the western portion now super saline and continuing to shrink each year. We visited the remnants of once thriving fish canneries and harbours; the steel carcasses of ships now surrounded by sand and salt tolerant shrubs. The edge of the Ustyurt plateau that once formed the western coast of the Aral Sea has now collapsed, with no water pressure holding the cliffs in place. This environmental catastrophe resulted from massive diversion of the Syr and Amu Darya rivers to grow cotton in the desert. Not many lessons have been learnt it seems, as highlighted by the hundreds of kilometres of unlined irrigation canals and major salinity across all the irrigated fields, and cotton production quotas unofficially still in place.

Our time in Uzbekistan brought to the fore reflections on the distinction between being a traveler and being a tourist. This distinction is a blurry one, but what was evident in Uzbekistan is that once a country becomes exposed to mass tourism, the experience of being a traveler changes as local populations become blasé with so many foreign faces around, and it becomes difficult to have relaxed non transactional interactions, if you do want to see the cities Uzbekistan is renowned for. In the end we need to accept that there’s a lot of people in this world with the money and desire to visit beautiful places, and we can’t reasonably expect to be visiting such places alone.

Still, we did have a few fantastic interactions, sharing laughs and a bottle of wine over google translate with our guesthouse host Karim, and being invited into a pottery studio and home for the night in Rishtan in the Ferghana Valley – most likely more than one could expect travelling in Europe!

We will remember Uzbekistan as a place of visual wonder, craftsmanship requiring infinite patience and skill, juicy mulberries picked fresh from the tree, and wonderful memories created with Nathalie